Books

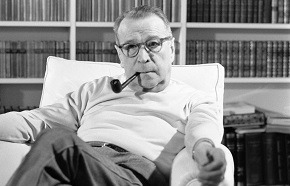

Jason Webster on Georges Simenon

None of the greats of crime writing have been as focussed on the poetry of their craft as the Belgian Georges Simenon. Where the centre of gravity in Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie is essentially the intellect, and in Raymond Chandler the physical body, Simenon’s writing springs from a realm of experience which we might call the ‘poetic self’. His books, not least his celebrated Inspector Maigret series, are rich with mood and atmosphere and hint at more than a simple crime and its solution. For Simenon, the detective novel is a format in which the writer can search for answers to questions beyond the simple ‘whodunnit’, probing at the matter of existence itself.

Simenon’s celebrity today rests in large part on his prodigious output – almost 200 published works, writing between four and six novels every year – and his legendary sexual conquests, claiming in old age to have made love to 10,000 women since the age of 13. These Olympian statistics have perhaps overshadowed his books in recent years and we have lost sight of the extraordinary quality – as opposed to mere  quantity – of his writing. At a time when longer and more spectacular crime novels are being demanded, his slim volumes and efficient, elegant prose may appear out of fashion. Yet it was his body of work on which he wished to be judged; his ‘big novel’, he insisted was ‘the mosaic of all my small novels’. If he were writing now, one suspects he would be with independent publishers, or even publishing his books himself.

quantity – of his writing. At a time when longer and more spectacular crime novels are being demanded, his slim volumes and efficient, elegant prose may appear out of fashion. Yet it was his body of work on which he wished to be judged; his ‘big novel’, he insisted was ‘the mosaic of all my small novels’. If he were writing now, one suspects he would be with independent publishers, or even publishing his books himself.

Central to everything Simenon wrote was what he called ‘the poetic line’. This was the feeling or atmosphere from which the characters, the story, the setting and everything in the novel was born. Sometimes he likened it to a colour, and he lived within its reality for the period in which he was writing the book – never more than ten or eleven days – often taking on the peculiarities of his characters while he got inside their skins, much like a method actor. These ideas originally came from somewhere in his subconscious: while taking a long walk he would see something that reminded him of a place or a person which would then become the trigger for the novel. He referred to this as being ‘in a state of grace.’

‘[I] empty myself of all preoccupations that personally affect me, the man called Simenon, so as to become a sort of sponge which can absorb other people’s personalities, live through other people’s memories, and finally bring them out again – breathe them out – in the form of literature.’

‘[I] empty myself of all preoccupations that personally affect me, the man called Simenon, so as to become a sort of sponge which can absorb other people’s personalities, live through other people’s memories, and finally bring them out again – breathe them out – in the form of literature.’

It was in this exceptional state that he was able, like the artisan he saw himself as, to carve out novels of powerful resonance populated by characters who live fully in three dimensions, who have, as he put it, a ‘poetic aura’.

Personally, what makes a Simenon novel so memorable is less what actually happens than this feeling and atmosphere that it evokes. Maigret might spend half the story simply following a suspect around Paris in the rain, and it is gripping because I am there with him in the smoke-filled bar, condensation dripping down the inside of the windows, watching for the man to make one tiny mistake that will give him away.

And I care because his characters have substance and weight and speak to me, like the characters of Borges, Stendhal and Dostoyevsky, in the searching, illuminating language of poetic truth.

Jason Webster is the author of the Chief Inspector Max Cámara crime series set in Spain. His latest instalment, Blood Med sees Cámara back in Valencia exploring the political and social problems of contemporary Spain.

Please note: Moderation is enabled and may delay your comment being posted. There is no need to resubmit your comment. By posting a comment you are agreeing to the website Terms of Use.